Research Areas

Studying the mechanisms of discogenic low back pain

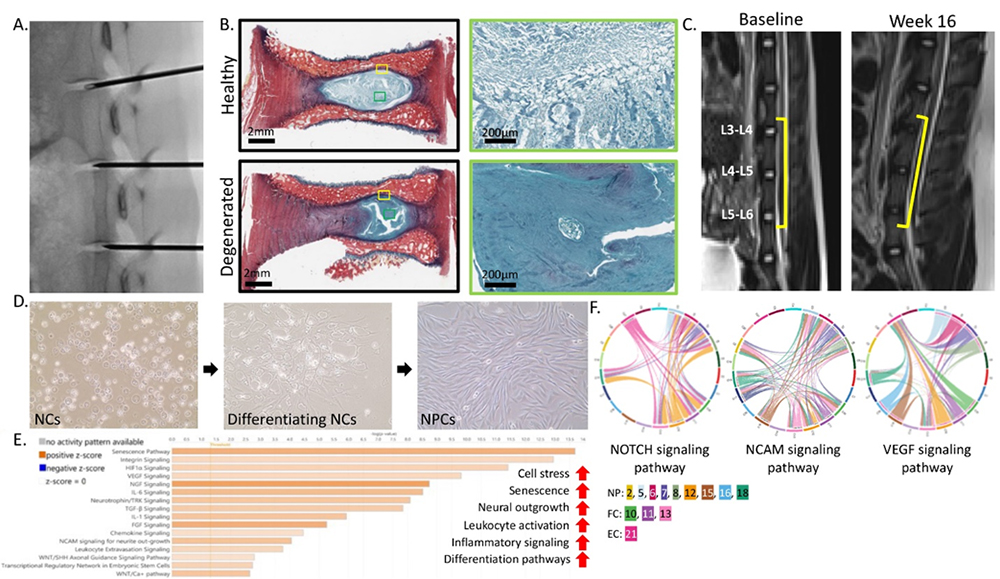

This study explores the mystery of low back pain, a widespread problem that often stems from aging and deteriorating spinal discs. We were curious about why some worn-out discs cause pain while others don't. We suspected that certain environmental factors might affect specific cells in the discs, leading to pain. To investigate this, the we compared tissue samples from painful and pain-free discs, using an advanced technique called single-cell RNA sequencing. We focus on a particular type of cell called nucleus pulposus cells (NPCs) and exposed these cells to various stresses in the lab. The key finding was that a specific group of stressed NPCs was linked to discs causing back pain. When these stressed cells were injected into rat spines, the animals showed signs of increased pain sensitivity.

This discovery is exciting because it reveals a potential trigger for low back pain at the cellular level. Understanding this mechanism could lead to more targeted treatments that focus on these specific pain-causing cells, rather than trying to repair entire discs. This approach could offer new hope for people suffering from chronic low back pain.

Figure 1. Concept overview of NPC-mediated low back pain development.

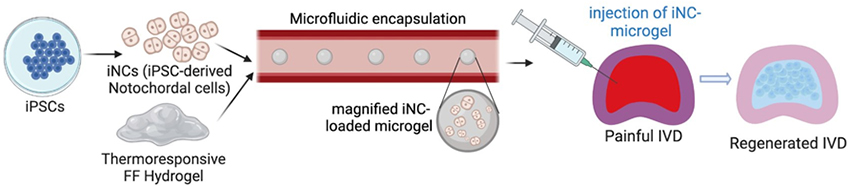

Understanding the role of notochordal cell differentiation in IVD degeneration and low back pain development in pigs

We have developed a pig model of lower back pain (LBP) in which we can measure pain development using non-invasive biobehavioral testing (BBT) and MR imaging. This model will serve as a tool to test new and emerging therapies for LBP and accelerate their development towards treatments that can be used in the clinic.

We are also using this model to better understand how LBP develops by studying changes at the cellular and molecular levels. Our findings show that, as the IVD degenerate, the main cell type in the disc shifts from stem cell-like notochordal cells (NCs) to fully mature cells called nucleus pulposus cells (NPCs). These mature cells seem to be involved in nerve growth, inflammation and other changes that may contribute to lower back pain. We are now studying how degenerative conditions affect NCs to uncover what causes them to change into NPCs.

Figure 2. Pig model development and notochordal cell differentiation. A: Fluorscopic imaging of disc injury. B: Picrosirius red and Alcian blue staining of healthy and degenerated IVD. C: MR imaging of IVD at baseline and week 16 post-injury. D: 2D culture of pig NCs differentiating into NPCs. E: Pathway enrichment analysis of NPC clusters. F: Select cell communication analysis pathways.

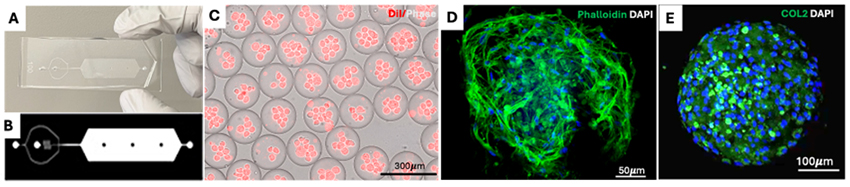

Microgel-encapsulated stem cells to alleviate low back pain

Current treatments for low back pain, such as surgical intervention and pain management, focus on alleviating symptoms of the disease without addressing the disease itself. Our lab is looking to develop a stem cell therapy to regenerate the degenerated IVD by leveraging microgel technology to safely deliver induced notochordal cells into the disc. By encapsulating cells within microgel we can inject the cells directly into the IVD without the need for surgery. The microgel also has added benefits of protecting the cells from the harsh environment of the degenerated IVD, the possibility of pre-conditioning the cells in vitro, and shielding the cells from sheer force exerted by pushing them through a syringe and needle. Research will be done in several pre-clinical models to determine the efficacy and safety of the microgel treatment. This study is funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) and the NIH HEAL Initiative.

Figure 3. Microgel encapsulation of nucleus pulposus cells. A-B: Sample layout of the microfluidic device used to encapsulate microgels. C: Phase image of DiI-labeled cells loaded into microgels within the microfluidic device. D: Fluorescence image of cells-loaded microgels stained with Phalloidin and DAPI. E: Immunofluorescence images showing collagen type 2 secretion inside the microgel (green) and nuclei stained with DAPI (blue)

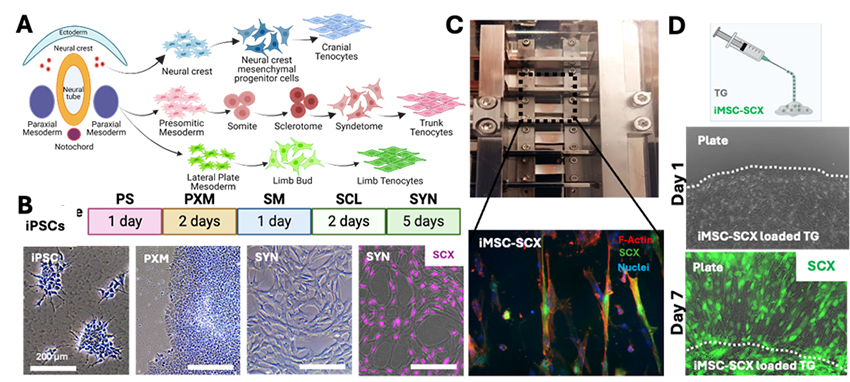

Developing stem cell therapies for tendon injuries

Tendon injury is one of the most prevalent musculoskeletal problems in the world with 4 million new incidents per year. The injured tendon never fully recovers the strength and functionality due to formation of scarring during healing. Development of a cell and tissue engineering approach for repairing tendons has the potential to dramatically improve patient outcomes by scar-free healing. In the Sheyn Lab, we focused on three main approaches: 1) Elucidation of the regenerative and inflammatory cells, and their fate in tendon healing by gait analysis, biomechanics and single nuclei transcriptomics, 2) Understanding 3-dimensional mechanical stimulation of cells in tendon development, and 3) Implementation of these information via the help of developmental pathways to produce induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC)-derived tendon cells as novel stem cell therapeutics. In addition, the transfer and bioavailability of the cells in the injury site poses a significant challenge. It is aimed to solve the cell implantation problem via two different ways depending on the severity of the tendon injury: 1) Mechanically stimulate and mature the tenogenic precursor cells in vitro and apply with the help of 3D scaffolds in ruptures, and 2) Load cells into thermoresponsive gels (TGs) and inject in surgically repaired tendinopathies such as tears.

Figure 4. A: Tenogenic pathways in embryogenesis. B: Developmental pathways followed in production of Syndetome (SYN) cells as tenogenic precursors. C: Achilles tendon full thickness transection non-repair model in rats applied to study tendon healing, biomechanics testing method and representative tendon mechanical testing results obtained 2 months post-operation. D. Scaffold-tenogenic iMSC-SCX model cell combination to study mechanical stimulation on tenogenic differentiation and change in orientation of cells parallel to stimulation direction. E: Thermoresponsive (TG) gels loaded with tenogenic cells to study injectable cell carrier application in tendon defects where cells can be loaded in thermally crosslinking gel at body temperature (37°C).

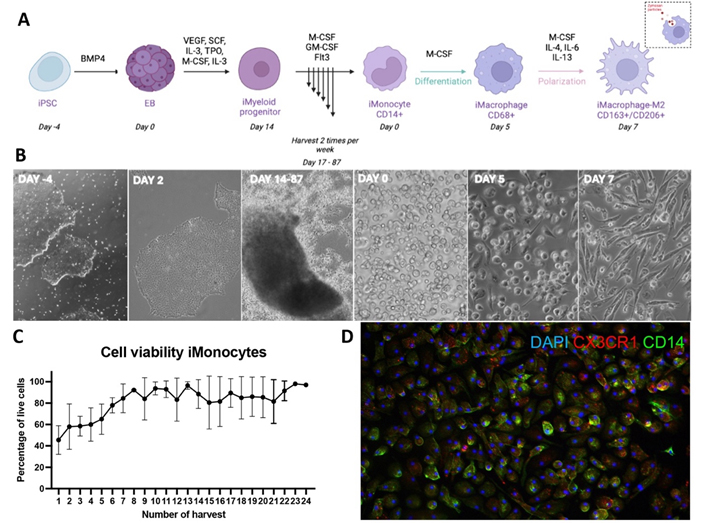

Human iPSC-derived macrophages as a potential preventive treatment for knee post traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA)

This study explores a new potential treatment for post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA), a painful joint condition caused by injury. Researchers used special stem cells to create anti-inflammatory cells called M2 macrophages. These lab-made M2 macrophages were tested in dishes with inflamed joint cells from osteoarthritis patients and showed promising results in reducing inflammation. The team then injected these cells into rats with simulated PTOA. Early results were encouraging: the treatment didn't cause immune reactions or increase pain. Using advanced imaging techniques, they found that the M2 macrophages might help slow down joint damage. This approach could lead to new ways to prevent and treat osteoarthritis by restoring balance between inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cells in the joints.

Figure 5. Stepwise induction of iPSCs to anti-inflammatory macrophages (iMac-M2). A: Schematic illustration of iPSC stepwise induction to iMac-M2. B: Representative brightfield images showing various differentiation stages. C: iMonocytes viability of per harvest. D: Immunofluorescent images of iMac—M2 expressing M2 markers.

Contact the Sheyn Lab

127 S. San Vicente Blvd.

Advanced Health Sciences Pavilion, A8308

Los Angeles, CA 90048